An economy’s potential depends on its resources, and the US economy’s most vital resource is its people. The US economy continues to expand, but it is hindered because growth in its aggregate supply has not kept up with growth in its aggregate demand. Record increases in income propelled the economy through the second quarter. But the economy’s growth has been limited because many people fearing COVID have chosen not to return to work. Shipping problems have also constrained aggregate supply. Inflation is the consequence when an economy’s aggregate demand increases at a faster clip than its aggregate supply.

To learn more about the US economy’s progress and where it is heading, read our summary of vital statistics and analysis.

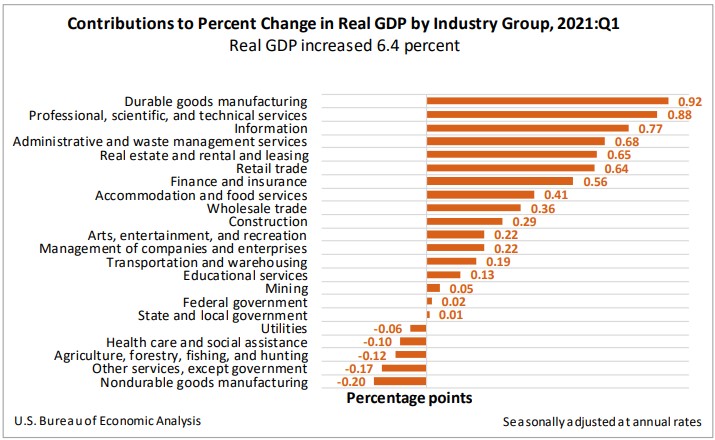

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) did not revise its estimate of RGDP in the first quarter from its second estimate. However, it raised its estimate of real gross domestic income (RGDI). Overall, the US economy gained momentum from the fourth quarter of 2020. Government transfer payments fueled it, and RGDP has almost reached its pre-pandemic level. Consumer spending was the primary driver. Manufacturing of durable goods contributed the most to the increase in RGDP. The table below provides a more complete list of the contributions in the first quarter. It will change significantly in the second and third quarters when the rebound in the service industries will become more evident. To access the full report, visit Gross Domestic Product, Third Estimate First Quarter 2021. The BEA will release its advance estimate for the second quarter of 2021 on July 29.

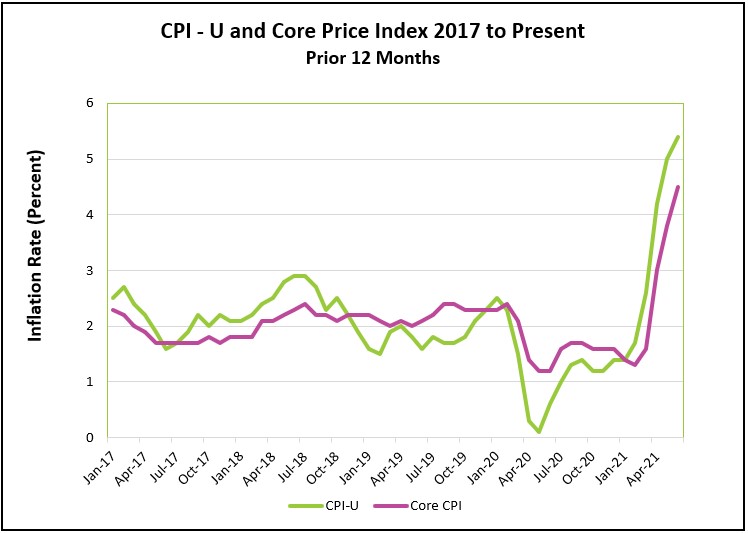

A sharp increase in the personal consumption price expenditures price indexes is fueling more concern about inflation. The index increased to levels it has not reached in nearly two decades. It exceeds the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%, but the Fed officials believe the increase is temporary. More detailed discussions concerning the recent price increases are included below in the Consumer Price Index and the Summary and Analysis sections.

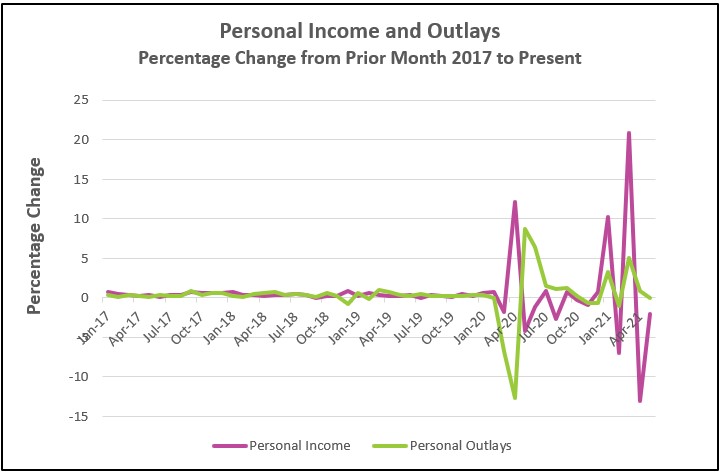

Consumer spending was flat in May after rising in April and March. Income fell. A significant drop in government transfer payments associated with the American Rescue Act explained both the decrease in spending and income. Spending patterns reversed as people continued to venture out more, causing a shift from spending on larger ticket items such as vehicles to recreational services. Read the full report Personal Income and Outlays – May 2021. The highlights are listed below.

Prices rose at the fastest pace in 13 years. Demand-pull and cost-push inflationary pressures were evident as the economy emerges from the pandemic. The largest increases were in industries that lowered their prices during the containment measures, or industries with supply chain challenges. Government officials insist that the pressure is short-term. Whether or not they are correct has enormous policy implications. Some are discussed below in the Summary and Analysis section. Read the complete report Consumer Price Index – June 2021. Here are the highlights of the report.

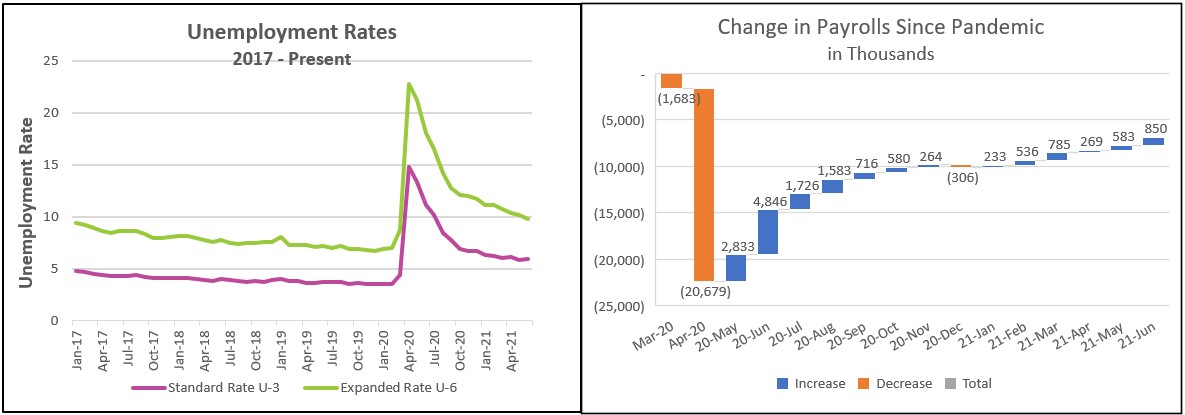

The unemployment rate increased slightly in June because more people are reentering the workforce. Businesses continue to seek workers. There are more job openings and fewer people willing to work than before the pandemic, which is putting upward pressure on wages. Employers are offering higher pay and more attractive benefits to attract workers. The highlights from The Employment Situation – June 2021 are listed below.

At the beginning of 2021, economists debated how to minimize the impact of a deep recession. Now, many are concerned that the economy is overheated, and the fiscal and monetary stimulus measures have been too successful. Inflation has become a concern. The US economy’s aggregate demand has surged, but its aggregate supply has not kept pace with the increase in demand, resulting in record economic growth, an increase in employment but also a record jump in prices. Higher incomes and accumulated savings funded by wages and government assistance have provided consumers with the funds to spend. And spend they have. During the early stages of containment, many people purchased durable goods such as improvements for their homes or a car. More recently emboldened by vaccinations and pent-up demand from months of confinement, they have increased their spending for services such as local restaurants.

Companies in the leisure and hospitality industries added 343,000 jobs in June but still employ 2.2 million fewer people than before the pandemic. Businesses continue to have trouble finding workers. Restaurants and other service businesses requiring low-skilled labor are struggling to rehire enough workers to meet their demand. Many are offering higher wages or a signing bonus, while raising their meal prices to pay for their added expense. Workers remain reluctant to return to the industry, even after employers have increased wages. Why have workers been hesitant to return when jobs are available? Many business owners and economists believe there is a disincentive to work because their unemployment compensation exceeds their wages. The breakeven income is approximately $32,000 a year. There is little incentive to return to work for those who earned less than that, especially if they are confident that they will find a job when the supplemental unemployment insurance ends in early September. Many older workers retired. The participation rate remains much lower than before the pandemic. Almost seven million fewer people work than before the pandemic.

But the job situation is improving. The unemployment rate increased slightly, but for a healthy reason. People returned to the workforce. A person is considered unemployed only if he or she is actively seeking employment. Payrolls increased 850,000, the largest increase since last August. The combination of a higher number of people employed and a higher unemployment rate is only possible if people are working or actively seeking a job. U-6 fell sharply last month. U-6 is a broader measure of unemployment that includes workers who work part-time but would prefer to work full-time, and people who are too discouraged to look for a job.

Inflation, whether measured by the Federal Reserve’s preferred PCE price index or the more often quoted consumer price index, far exceeds the Federal Reserve’s target rate of two percent. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell testified last week that he is surprised and concerned by the recent significant jump in prices, but he believes the inflation rate should subside in a few months. He also assured Congress that the Federal Reserve would take measures to reduce inflation and slow economic growth if current levels persist. However, along with most of the Federal Reserve’s governors and President Biden’s economic team, he believes the base effect overstates the inflation figures – because prices dropped a year ago, they have a lower base, so inflation is overstated. For example, airline fares rose 2.7% in June but remain less than before the pandemic. Hotel room rates have returned to pre-pandemic levels after increasing 7% in June.

The inflation indexes were also weighted heavily by price increases in a few goods that COVID-19 significantly impacted. Many of these goods and services had great pent-up demands, which should return to normal in several months. In other cases, supply chain issues directly caused by the pandemic increased manufacturing costs. For example, used car prices rose 45% in the prior 12 months. In June, they contributed over one-third to the jump in the consumer price index.

Restaurants provide an example of how a pent-up demand and supply challenges have combined to trigger higher dining prices. While the demand for dining out has increased, restauranteurs are also faced with higher food prices and labor costs. (Meat prices rose 3.1% in June. Hourly wages for restaurant and hospitality workers are 7.9% higher than in February 2020.) Many restaurants have responded by increasing their prices to reimburse their higher costs and meet the demand increase. The price of a meal at a full-service restaurant increased by 0.8% in June. Other businesses in the leisure and hospitality industries that suffered greatly during the pandemic have also experienced a growing demand and increased labor costs.

Excessive inflation hurts families on a fixed income and people whose earnings rise less than the inflation rate. Businesses are hit with higher costs and may not be able to raise their prices. Interest rates usually rise during inflationary periods. First, lenders increase their nominal rates to compensate for lower real (after inflation) returns. Second, the Federal Reserve typically increases rates to slow the inflation rate. The threat of higher inflation may jeopardize the passage of President Biden’s spending package. Much also depends on the supply of labor. Will people return to the workplace? The Fed is hoping they will. A shortage of workers would continue the upward pressure on wages. Rising pay and prices can feed on one another. Prices increase. Workers negotiate a higher wage to offset the higher cost of living. Companies increase prices to pay for their higher labor cost. In the 1970s, when inflation was prevalent, rising wages and rising prices spiraled out of control – that is until the Fed induced a recession. Ultimately, fewer workers also mean less money circulating through the economy, which can slow economic growth.

The international markets may also hamper growth. The US economy has prospered more than most other countries, largely because of government stimulus payments. Sadly, only one-eighth of the world’s population is fully vaccinated. If Covid continues to disrupt these countries, supply chain challenges will persist. Many of these economies are not as resilient as the US economy. Downturns in them will adversely impact US exports.

Later this month, the BEA will confirm the US economy is growing at a near record clip when it publishes its advance estimate for the second quarter of 2021. Some economists will describe the economy as being overheated. If the FOMC agrees, then the Fed will begin to raise interest rates sooner. To make your own evaluation, pay close attention to those items you purchase with the largest price increase. Are they goods and services that suffered during the pandemic? Have supply chain issues impacted their delivery? If the answer to these questions is “yes,” then chances are inflation will subside. But if the answer is “no,” then inflation has become more widespread. Economists and investors will pay close attention to employment figures. Will people return to the workforce? If not, will businesses continue to increase wages to attract employees? If so, will the increase in workers be sufficient to reduce wage inflation? The Fed has made it clear that it does not want to slow the recovery before the employment situation improves but that it is willing to step in if it believes inflation is persistent. The answers to these questions will determine the Fed’s direction.